A detailed appraisal of global energy system jobs and the impact of different climate and energy policy pathways in a study realized by the RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment in collaboration with researchers from the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, and Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg. By 2050, jobs in the energy sector would grow from today’s 18 million to 26 million under our well-below 2°C scenario. Robust climate policies would increase global energy sector jobs because while the majority of fossil fuel jobs could be lost as those sectors decline, in many parts of the world these jobs could be offset by gains in renewable energy jobs.

Over 12 million people work in the coal, oil and natural gas industries today. However, to keep global warming well-below 2°C, a target enshrined in the Paris climate agreement, all three fossil fuels need to dramatically decline and be replaced by low carbon energy sources. Such a shift in energy systems would have wide-ranging implications beyond meeting the climate target. While this is technically possible, whether it can be done fast enough is a political question. One major factor influencing political support for climate policies, particularly in fossil fuel producing countries, is the impact they have on fossil fuel jobs.

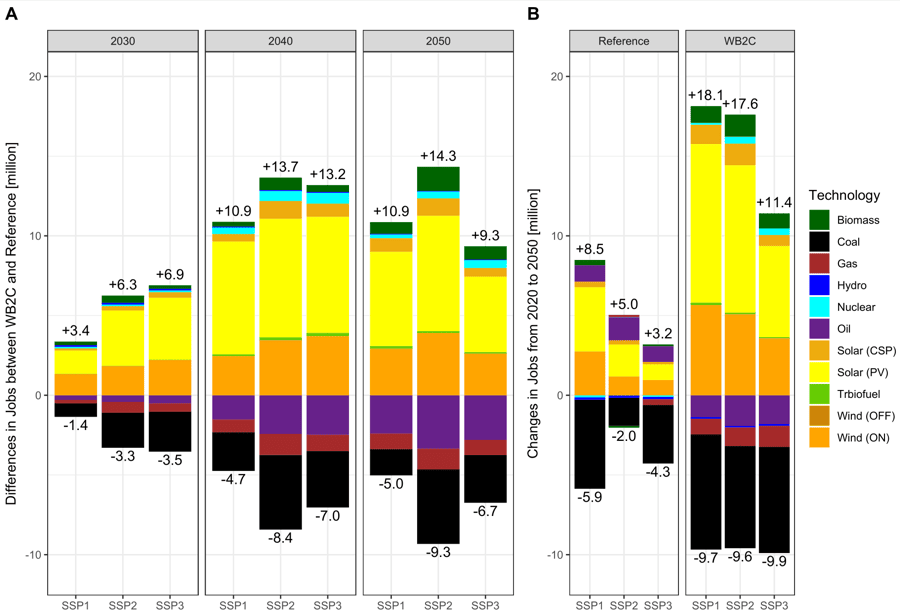

A study realized by RFF-CMCC European Institute on Economics and the Environment and just published in the journal One Earth shows that stringent climate policies consistent with keeping warming well-below 2°C would increase global energy sector jobs by about 8 million by 2050, primarily due to gains in the solar and wind industries.

“Currently, an estimated 18 million people work in the energy industries—a number that is likely to increase, not decrease, to 26 million if we reach our global climate targets,” says Johannes Emmerling, Head of the Low Carbon Pathways Unit at EIEE and corresponding author of the study. “Manufacturing and installation of renewable energy sources could potentially become about one third of the total of these jobs, for which countries can also compete in terms of location.”

Researchers built a new global dataset of employment factors in 50 countries by technology and job category and used an integrated assessment model (IAM) to investigate the impact of the global climate targets of well-below 2°C on energy sector employment by energy technologies, job categories and regions. Specifically, they focused on quantifying the impact of energy system changes on “direct jobs”, or jobs that relate to core activities involved in energy supply chains since these jobs are most closely correlated with the growth and decline of energy technologies.

“The energy transition is increasingly being studied with very detailed models, spatial resolutions, timescales, and technological details,” says Emmerling. “Yet, the human dimension, energy access, poverty, and also distributional and employment implications are often considered at a high level of detail. We contributed to fill this gap by collecting and applying a large dataset across many countries and technologies that can also be used in other applications.”

Of the total jobs in 2050 under the well below 2°C scenario, 84% would be in the renewables sector, 11% in fossil fuels and 5% in nuclear. Moreover, while fossil fuel jobs, particularly extraction jobs, which constitute 80% of current fossil fuel jobs, would rapidly decline, these losses would be more than compensated by gains in solar and wind jobs. A large portion (7.7 million in 2050) of the growth in solar and wind jobs would be in manufacturing jobs which are not geographically-bound, and which could lead to competition between countries to attract these jobs. Results show how regionally, the Middle East and North Africa, and the US could witness a substantial increase in overall energy jobs with renewable energy expansion, but China may see a decrease with a decline of the coal sector.

In the European Union there would be overall job increases in both WB2C and Reference scenarios compared to today, but the percentage increase depends on the SSPs led pathways this region follows.

“Understanding these potential job shifts is important for a couple of reasons”, the authors write. “First, in economies where fossil fuel production and exports are important, political support for low-carbon transitions increasingly centers around the debate of ‘jobs vs the environment/climate’ and it is important to know the impact such climate action may have on what are often politically salient jobs. Many politicians support fossil fuel industries due to the importance of the associated jobs. For example, in the 2016 US presidential election, candidate Trump, referred to coal miners 294 times and campaigned on a platform of reviving the coal industry and coal jobs. Second, green politicians and environmental groups argue that taking bold climate action, including phasing out fossil fuels, can go hand in hand with a ‘just transition’ for fossil fuel workers that includes retraining these workers to renewable energy jobs. However, any just transition program needs to understand the scale of shifts of jobs away from fossil fuels. Additionally, left and green politicians along with environmentalists are interested in understanding the scale and scope of potential renewable energy jobs under a green economy.”

Figure 1: Gains and losses of jobs per energy technology

The figure shows the changes in energy sector jobs by energy technology comparing different scenarios

(see axis description) and across the different SSPs.

Credit: Pai et al./One Earth

For more information:

Pai et al., Meeting well-below 2°C target would increase energy sector jobs globally, One Earth (2021), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2021.06.005

https://www.cell.com/one-earth/fulltext/S2590-3322(21)00347-X